There are a number of significant archives of South African music in various institutions and private collections across South Africa and indeed around the world. Many of these entities have made great efforts to digitize the sound component of their collections but, interestingly, not the visual artifact itself—the object that carries the sound.

Naturally the primary focus of any music collection should be the music. For me, however, the visual components—the covers and even labels—of any recording can reveal much information or meta-data that can be useful if linked back to the audio. The images of labels alone, for example, carry significant information about graphic design histories: what fonts were used during which periods; how colors and label design are employed to differentiate and brand music styles or target various audiences and subsequently consumers; how coupling prefixes can categorize music styles. At the very least, matrix numbers can often aid in the dating of recordings and even illuminate such esoteric details as the identity of recording engineers.

It is possible that other nuanced micro-data may reveal more information for future researches, perhaps in unconventional ways. For example, when viewing a large set of images in a batch desktop application such as Adobe Bridge, visual patterns and shifts can uncover something about the whole label series that may not be evident when looking at any single label image.

With this in mind, I began documenting my own South African records around 2005. With access to online auction sites such as eBay and various encounters with antique dealers and junk shops, the collection gradually expanded. This endeavor became a useful tool for me to re-educate myself about the complexities of South Africa’s turbulent history through the lens of audio recordings, while enjoying some fantastic sounds.

With this in mind, I began documenting my own South African records around 2005. With access to online auction sites such as eBay and various encounters with antique dealers and junk shops, the collection gradually expanded. This endeavor became a useful tool for me to re-educate myself about the complexities of South Africa’s turbulent history through the lens of audio recordings, while enjoying some fantastic sounds.

Much of this music history, however, was still opaque to me, and for the broader public remained unmapped. I needed a tool to cross-reference the links between artists, their complex relationships with record companies, and at the very least a vehicle that could build dynamic discographies—a searchable database that was also visually appealing. At some point it became necessary to construct a website to host this visual archive and in 2010 I launched the South African Audio Archive at flatinternational.org.

At that time there were already a number of blogs and websites dedicated to South African music including: Matsuli, Electric Jive, Afro-Synth, Soul Safari, 3rd Ear’s Hidden Years Archive Project (HYMAP) and SAMAP to name a few.

The South African Music Archive Project or SAMAP has probably the most extensive database of Southern African music featuring well over 13,000 audio samples from six collections including the Ballantine Collection, HYMAP, Shifty Records and ILAM. The project developed around 2007 in partnership with Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) and went online in 2009.

As a visual artist, I found the experience of searching SAMAP useful but also frustrating. I wanted to be able to view the original artifacts while listening to the digitized tracks but SAMAP did not have the funding to visually document each record source. In my research, I found that a number of the participating institutions also had not photographed their collections. So I embarked on a project to do just that.

My project was straightforward: I would donate my time and modest photographic skills to document these and any other collections I came across. The particular institution would receive a set of the images and in return I would gain a visual knowledge of the scope of each of the collections. Using flatinternational to map the images, my plan was to crosslink these with the SAMAP database. Thus reconnecting image with audio across two databases while expanding the searchable footprint for applications like Google.

In 2012 I approached Christopher Ballantine with a proposal to document his collection. Ballantine, the LG Joel Professor of Music Emeritus at the School of Music, University of KwaZulu-Natal, had built his archive of significant 78 rpm records while researching his classic publication Marabi Nights: Early South African Jazz and Vaudeville (first published by Ravan Press in 1993). Ballantine has since greatly updated and expanded this seminal text and a second edition is now available as Marabi Nights: Jazz, ‘Race’ and Society in Early Apartheid South Africa (UKZN Press, 2013). This award winning book is accompanied by a compact disc containing 25 excellent tracks of South African recordings from the 1930s and 40s. The earlier, first edition came with the same tracks on a cassette tape.

|

| The Christopher Ballantine Collection, School of Music, University of KwaZulu-Natal |

In August 2012, Kendall Buster and I visited Chris Ballantine’s office in Durban and he kindly allowed us to photograph his entire collection of roughly 500 shellac discs over two days. That same year I also documented a significant portion of (my Electric Jive colleague) Chris Albertyn’s 78 rpm collection in Durban.

If you navigate to the search page of flatinternational and type "Ballantine" into the source field you will see a list of interesting examples from the collection. The results also give a sense of how the visual discography works. Select a disc and then select a track. You will be taken back to the SAMAP page where you can listen to the track. At the moment there are only a few discs represented from the collection at flatinternational. But it is my hope that, in time, more will be added.

The story behind ILAM is itself interesting. In 1947 Hugh Tracey was hired by Eric Gallo to run African Music Research (AMR), a unit funded by Gallo Africa Limited with Tracey as director. Through this relationship, Gallo supported Tracey’s early recording expeditions throughout sub-Saharan Africa allowing him to build a substantial archive of African recordings. The relationship was mutual, Gallo would reap the financial benefits of any successful tracks that Tracey might find while enabling Tracey to continue his research into African music.

Tracey established the African Music Transcription Library (AMTL) that housed the field tapes from these expeditions as well as his broader archive of materials collected while he was director at the Natal studios of the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) from 1936 to 1947.

By 1953, Tracey felt a need to “relieve Mr. Gallo of his financial responsibility”, and established a more independent organization for his research. With the aid of a grant from the Nuffield Foundation that was then matched by various mining interests in Southern Africa, he established the International Library of African Music (ILAM) as a non-profit organization.

The work on the new library began in mid 1954. Though it is not clear to me whether Tracey continued to rent the premises that became ILAM from Gallo or build the library at a separate site. Both the former AMR and the new ILAM library were located at Msaho in Roodepoort.

Tracey, now as ILAM, continued his research into African music and began issuing the results of his many expeditions on the, now famous, Sound of Africa series consisting of 210 vinyl LP records. Earlier, more commercially viable recordings were also issued as 10” vinyl discs on the Music of Africa series and made available internationally on the Decca and London labels as well as Gallotone in South Africa.

|

| Hugh Tracey sorting records from his Sound of Africa and Music of Africa series, early 1960s. |

After Tracey’s death in 1977, ILAM was run by his son Andrew Tracey who, subsequently in 1978, relocated the organization to its current site at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. Today the archive's Director is Diane Thram, who assumed the position in 2005 after Andrew Tracey retired. In addition to what is a massive repository of African music and a fascinating collection of musical instruments, ILAM is also an active research institution attached to the Department of Music and Musicology and through them offers courses in Ethnomusicology.

Kendall Buster and I visited ILAM between July 14-17, 2015 just after the Grahamstown Arts Festival. We met with Diane Thram, who kindly toured us around the library and introduced us to a number of key people. We met Elijah Madiba, the sound engineer who was also responsible for the digitization project undertaken in 2007 that lead to the SAMAP database, as well as Liesl Visage, who both greatly facilitated the realization of our project.

|

| Elijah Madiba and Siemon Allen in the ILAM Archive, July 2015. |

With just three days in a bitterly cold Grahamstown our plan was ambitious. There was no way that we would be able to photograph every record in the collection. But given that my main area of research covers Southern African artists and South African companies, we decided to limit our focus to commercial 78 rpm recordings that met those criteria. There are, of course, multiple central African labels such as Opika, Ngoma, Jambo in the ILAM archive and in these cases we photographed only one disc from the set as an example of the label and a marker for future documentation.

|

| Elijah Madiba and Siemon Allen. Behind are the master tapes for the Music of Africa series. |

We arrived on Tuesday afternoon and spent the time setting up our photographic equipment and shooting a range of samples to determine the best exposures for various label colors, carefully making a list noting the ideal f-stop for each tone. But when we returned the following morning ready to begin our task, we found the building without power. At the time South Africa was in the grips of an energy crisis and the government had devised a solution for energy sharing known as load-shedding where power was turned off in various communities throughout the country on a rotational basis. Sometimes this process was structured and predetermined, but more often it was unexpected and of uncertain duration.

With the goal of finding an alternative source of light without removing our operation from the dark archival cocoon of the library, we spent the morning in downtown Grahamstown, investigating various hardware and specialty stores. We eventually found a potential solution at the local SPAR. Though far from ideal, our ‘Magyver plan’ involved fixing two battery-powered LED camping lights on either side of the copy stand. The camera was, thankfully, already battery powered. The LED lights were relatively dim and could only highlight a small circle roughly the size of the label area but it was good enough to get the critical information, albeit at a much lower camera speed and the risk of blurry images. The main lights did not come back on until late afternoon and by then, with our camping light rig, we had made considerable progress.

|

| Gallo advertisement for 78 rpm record storage shelf, c1951 |

A curious anecdotal detail I discovered while researching this post is that the shelving system used by ILAM employs the same original unit advertised by Gallo in Tracey's Librarian's Handbook, published around 1951.

Over the next three days we took over 3000 photographs, thankfully completing the task of documenting most of the commercial 78s, which alas amounted to just one wall of the storage room. The collection of course is significantly more extensive and we photographed limited examples of other materials in the collection. Below I have outlined some of the more interesting finds from the commercial 78s and the broader collection.

|

| Hugh Tracey with the Chipika Singers, ABC studios, Johannesburg, July 1930. |

Tracey’s first exercise in documenting African music was to facilitate the recording of some of the earliest “authentic folk” music from Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). At the end of July 1930 he brought nine Karanga men on a lorry from Fort Victoria to the studios of the African Broadcasting Company (ABC, then the private precursor to the SABC) in Johannesburg to record with a portable field recording unit that had sent by the UK-based Columbia Graphophone Company. With commercial intentions, the unit had come on the invitation of Polliack and Company, Limited who were the agents for Columbia in South Africa. Tracey’s trip with the men was aided by a grant from Witwatersrand University, through Percival Kirby, a professor there in the Department of Music. After the Columbia session the singers visited Kirby's office at WITS where they made further private recordings.

The Columbia engineers cut at least twelve tracks (six discs) with the group that became known as the Chipika Singers and were issued on Columbia’s mid-price, light-green Regal label. ILAM has five of these discs in their collection. The date of these recordings in many publications and in the ILAM meta-data for the photograph above is incorrectly attributed as June 1929. Interestingly the label of GR 38 has a small hand-written note in pen: "JHB. 1928." The "8" has been overwritten with a "9" at a later time in a different pen and then signed "HT". It is probably from these notes that Tracey was able to recall the date, though given that there was some confusion between 1928 and 1929, both dates must have been written long after the records came into his possession, as the correct date from Kirby and newspaper accounts is late July 1930. (Thanks to Rob Allingham for insisting on the correct date and leading me to the newspaper articles.)

The collection also includes 159 discs from Tracey’s first field expeditions undertaken in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) between June 1932 and July 1933. These recordings were embossed on plain aluminium plates with a diamond stylus using a very early portable machine. Tracey had received a Carnegie Fellowship grant for the project, through the aid of Harold Jowitt, then director of Native Development. According to his own accounts, he did not have the capabilities of preserving these fragile discs on tape at the time. And eventually they deteriorated to a point beyond making digitisation possible. Roughly 600 tracks altogether were recorded of rural material in languages such as Karanga, Zezeru, Korekore and Ndau.

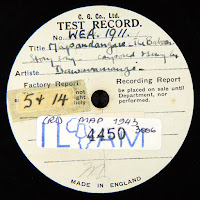

When the Columbia field unit returned at the end on 1932, Tracey again arranged to bring sixteen Karanga men in January 1933 from Fort Victoria to Cape Town via train to record. Roughly thirty pressings were issued on Columbia’s ochre-coloured, AE and YE series label. Only eleven of these discs remain in the archive today. More significantly though, the collection does have 63 single-sided test pressings with their original WEA matrix numbers from these recording sessions. We photographed a small selection of these, but at some point it would be important to return and document the rest.

When the Columbia field unit returned at the end on 1932, Tracey again arranged to bring sixteen Karanga men in January 1933 from Fort Victoria to Cape Town via train to record. Roughly thirty pressings were issued on Columbia’s ochre-coloured, AE and YE series label. Only eleven of these discs remain in the archive today. More significantly though, the collection does have 63 single-sided test pressings with their original WEA matrix numbers from these recording sessions. We photographed a small selection of these, but at some point it would be important to return and document the rest.

By many accounts, the first broadcasts in any African language in South Africa were made by King Edward Masinga on December 21st, 1941 (dates and accounts differ and some sources point to the Zulu Versatile Company as an earlier precedent in the 1920s). As the story goes that night Masinga read the 7pm news in Zulu from the Durban studios of the SABC after earlier in the day walking serendipitously past the building on Aliwal Street, entering, and approaching the director about a job. The director of the SABC in Durban at the time was Hugh Tracey. Masinga would go on to play a major role in South African broadcasting, including the translation of Shakespeare into Zulu for radio. In April 2015 he posthumously received a life-time achievement award at the annual MTN Radio Awards.

In 1944 Tracey and Masinga collaborated on a uniquely bilingual project and published a play—Chief Above and Chief below—in Zulu and English. Written by Masinga, the story is the retelling of an old Zulu legend, that is accompanied by dances and songs, also written by Masinga. (The book pictured above is from the flatinternational archive.) ILAM does have what appears to be radio broadcasts of the play from 1944 on a number of steel acetate discs. The discs are dated between December 20, 1943 and March 18, 1945 and it is my guess that the play was presented as a weekly or monthly radio serial. Notably, the discs carry the Gallo logo and the imprint of African Music Research (AMR) from Tracey’s time at Gallo in the late 1940s and early 1950s. My speculation is that these acetates are later transfers made by Tracey from an earlier format.

In 1944 Tracey and Masinga collaborated on a uniquely bilingual project and published a play—Chief Above and Chief below—in Zulu and English. Written by Masinga, the story is the retelling of an old Zulu legend, that is accompanied by dances and songs, also written by Masinga. (The book pictured above is from the flatinternational archive.) ILAM does have what appears to be radio broadcasts of the play from 1944 on a number of steel acetate discs. The discs are dated between December 20, 1943 and March 18, 1945 and it is my guess that the play was presented as a weekly or monthly radio serial. Notably, the discs carry the Gallo logo and the imprint of African Music Research (AMR) from Tracey’s time at Gallo in the late 1940s and early 1950s. My speculation is that these acetates are later transfers made by Tracey from an earlier format.

Amongst the commercial 78s themselves, one of the most interesting finds was a Homophon Company disc—up until then—a label I was not familiar with, let alone even aware that they recorded any South African related material. When I found this disc, I knew immediately that there was something significant about it. I asked Elijah Madiba if I could listen to the tracks. Alas, ILAM had not yet digitised them. So I embarked on some research around the meta-data associated with the disc

The double sided disc includes two tracks, one by Dr. W. B. Rubusana titled Kaffir Clicks and the second, O come Maidens come by Palmer Mgwetyana. About this word “kaffir” and its appearance here. It is a highly offensive, derogoratory term used to refer to black South Africans, notably during the apartheid era. The origin is Arabic meaning literally “non-believers”. (Interestingly, today one can sometimes hear the term in ISIS videos used when referring to “infidels”). Whether its appearance in this record title is intended as a deliberate racial slur or not, it’s seemingly 'benign' casual use (not unusual for 19th century publications) still gives a jolt to the contemporary researcher.

While both titles appear in English, the attributions on each side are not. "Sitewetu ngu..." and "invunywe ngu..." seem to be spelt phonetically in Xhosa as if the recording engineer wrote down word for word how the performers chose to present themselves in their own language. Perhaps their intentions were that these records would eventually be marketed back in the country of origin—Homophon discs were certainly advertised in South African media of the day. I asked Elijah Madiba about these attributions and said that "sitewetu ngu" translates as "narrated by" while "invunywe ngu" is "sang by".

“Kaffir Clicks” could refer to the Xhosa language likely spoken by Rubusana and so it is my guess that this side of the disc represents spoken word examples of Rubusana's style of speaking rather than songs. A 'curiosity' perhaps for what I assume was a British audience. Something, I suspect, not that dissimilar from how Western audiences responded to Miriam Makeba’s “Click Song” 50 years later.

“Kaffir Clicks” could refer to the Xhosa language likely spoken by Rubusana and so it is my guess that this side of the disc represents spoken word examples of Rubusana's style of speaking rather than songs. A 'curiosity' perhaps for what I assume was a British audience. Something, I suspect, not that dissimilar from how Western audiences responded to Miriam Makeba’s “Click Song” 50 years later.

Homophon was a German record label—the discs were pressed in Berlin—though the company had offices in London prior to World War One. On each side there are four distinct numbers: the overall catalog or coupling number (991), a matrix for each track (60174 and 60206), and then two additional alpha-numeric numbers in the lead-out of the shellac. Thanks to some esoteric notes available at normanfield.com I was able to determine that these numbers refer to dates. Though Homophon has a rather Byzantine dating system, this is still better than most 78 rpm discs that have none at all. Rubusana’s recording has G28P, which translates to July 28, 1911, while Mgwetyana has G31P or July 31, 1911. While it is not clear whether these represent the actual recording dates, I suspect that they almost certainly do. The fourth number, 1913A, also refers to a date, 1st September, 1913, but it is unclear whether this represents a pressing or issue date.

Both Rubusana and Mgwetyana were part of a South African delegation that attended the historic first Universal Races Congress held over four days at the University of London from July 26-29, 1911. The meeting, with 2100 attendees, had been organised by the Ethical Culture Society to discuss the state of race relations across the world and included participants such as W.E.B. du Bois. I am almost certain that these recordings were made while these two men attended this historic meeting in London and that the numbers on the shellac refer to the specific recording dates.

Dr. Walter Benson Rubusana was a notable South African leader and sometime political rival of John Tengo Jabavu. Interestingly Rubusana become the first black African ever elected to serve as a member of the Cape Provincial Council. He was elected president of the South African Native Convention in 1909 before becoming one of the vice-presidents of the organisation that became the African National Congress after attending their inaugural conference in Bloemfontein in 1912.

The Homophon recording is one of, if not the first of any South African political leader, black or white. While it is likely that the record was issued in 1913, it is significant that the recordings predate Zonophone’s historic 4000 series of South African material launched in 1912. Within the history of black Southern African recordings these two tracks are only preempted by the mostly religious tunes cut in 1907 by the Swazi Chiefs and issued on the Gramophone Concert Record (GCR) label.

I found it odd that Hugh Tracey, as one of the earliest collectors of African music did not have any Zonophone and GCR discs in his collection. However, this Homophon disc qualifies as the oldest recording in the ILAM collection. In my view it is a recording of great historical significance and warrants further research.

Many thanks to ILAM, Diane Thram, Elijah Madiba, Liezl Visagie and Chris Ballantine for making this project possible.

Thanks Siemon for documenting and sharing this.

ReplyDeleteThanks Chris! Talk soon!

DeleteFascinating reading! I am very much looking forward to more. Your insight and hard work is amazing.

ReplyDeleteFantastic! Fred Spider- Voom Voom Records - Cape Town

ReplyDelete