“Don’t let this picture fool you. It is the somber, dolorous and docile portrait of a lively bubbling brook of hep cat, Mabel Mafuya. The jazzingest twenty-four inch waist I’ve seen in a recording studio. And what can you get in a wiggly waggly twenty-four inch waist that heps and jives and dashes behind partition to rehearse the next verse in the middle of the recording session? Lots. You get her Troubadour AFC 353 that paints the grim grime of a miner’s life in jumping tones.” (Drum, February 1956)

David Coplan uses this fragment of Todd Matshikiza’s 1956 review in Drum magazine to illustrate Matshikiza’s style of “word jazz”. But the text also paints a wonderful portrait of a young Mabel Mafuya, who in the mid to late 1950s was one of South Africa’s top-selling jive vocalists. At Troubadour, Mafuya was only second to Dorothy Masuka, and in the mid to late 1950s Troubadour dominated the African market with at times up to 75% of sales. (Rob Allingham, CD liner notes, Dorothy Masuka)

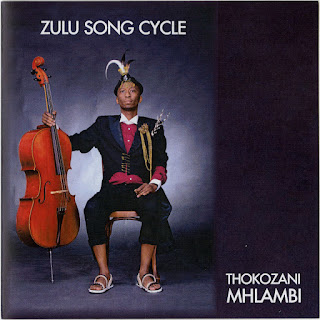

|

| Mafuya in 1993 by Mike Mzileni |

Mafuya’s destiny as a star seemed to be set in a fortuitous meeting, that Z.B. Molefe describes in A Common Hunger to Sing, when as a young teenager in Orlando she passed by her idol Dolly Rathebe. At that moment Rathebe happened to toss aside a half eaten apple. Mafuya picked it up and took a bite. In her interview with Molefe she recalls: “My mind and heart told me that if I bit that apple where the great Dolly had bitten, I would grow up and sing like her one day.” (Molefe)

That destiny was soon confirmed. While Mafuya was still a student at Orlando High School around late 1955 or early 1956 Cuthbert Matumba, producer and talent scout for Troubadour Records invited her to make some recordings at their studios. There she would soon rub shoulders with another of her idols, Dorothy Masuka, who would also became a mentor to her in those early days.

At Troubadour, Mafuya became one of the regular artists brought in to record not only her own compositions but also as a group and/or backing vocalist with a number of other artists including Dorothy Masuka, Dixie Kwankwa, Doris and Ruth Molifi, and Mary Thobei. The company had a roster of artists who rotated and recorded under a number of different pseudonyms and the groups Mafuya performed with included the Girl Friends, the Satchmo Serenaders, Starlight Serenaders, Starlight Boogies, the Starlight Singers, and others.

Mafuya appeared as a backing vocalist on a number of songs by Dorothy Masuka, notably one of my all-time favorite tunes, Five Bells, recorded September 3rd, 1956. But her career really took off with the hits Nomathemba and Hula Hoop recorded with her group the Green Lanterns that same year. Rob Allingham describes Nomathemba as her masterpiece in that the “song’s narrative of broken ties […] encapsulated the dislocating experience of rural-to-urban migrancy for many township residents.” (Allingham, CD liner notes, History of Township Music)

Interestingly, Nomathemba has been at the center of a recent legal battle over copyright between Sting Music and Gallo Records. A song called Nomathemba was used in the stage production Umoja. Gallo claimed that it was originally released by Ladysmith Black Mambazo on their debut LP in 1973. The plaintiff claimed that the song was traditional, free of copyright and pointed to a number of earlier examples including Mafuya’s 1956 version. That version was written by Zachariah Moloi, one of the Green Lanterns, but is not clear to me whether the song is the same as that composed by Joseph Shabalala. Read more about the court case in the Sowetan.

The social references in Mafuya’s Nomathemba were typical of a number of her songs from this period. In fact, where other record companies shied away from political or social content, Troubadour openly embraced it. Matumba often encouraged critical or topical commentary in the recordings during this period, and despite visits by the Police "Special Branch," remarkably the owners of Troubadour did not temper the activity. (Allingham, CD liner notes, Dorothy Masuka)

Troubadour was initially founded in 1951 by three and then later two Jewish businessmen, Morris Fagan and Israel Katz. Their approach was to focus on material that appealed to working class urban blacks, a market that was going through quite a renaissance in the 1950s. (Allingham) Still, the political environment in South Africa at this time was particularly turbulent. Sophiatown, one of the key centers of cultural production for a multi-racial community, had just been dismantled in February 1955 by the apartheid government, making way for a new white area soon to be called Triopf. The Treason Trial had begun after 156 people including Nelson Mandela were arrested in December of 1956. Nevertheless, music that carried a political message was able to get through to the public, either by record sales or less frequently by way of the rediffusion service, a cable based radio system available to blacks in some townships. This of course was the case until the Sharpeville massacre of March 1960, which resulted in a severe increase in censorship and self-censorship of political content.

The compilation opens with a 1956 track Regina, a homage dedicated to Regina Brooks, a white woman who had been arrested under the immorality act for having a child with a black policeman. In 1955 Brooks became controversial after she asked to be re-classified as coloured (or mixed-race) in order that she could live in Orlando, Soweto (some sources have it as Dube) with her husband, Sergeant Richard Kumalo, and child. Drum photographer, Bob Gasani captures Brooks and her child, Thandi, in this 1955 image sourced from the Bailey Archives. Read more at IOL.

|

| Regina Brooks and Thandi in 1955 by Bob Gasani (Bailey Seipel Gallery) |

Mafuya’s homage to individual heroes was also not unique in the case of Regina Brooks. After the suicide of Ezekiel ‘King Kong’ Dlamini on April 3rd, 1957, Mafuya and her Troubadour colleague Mary Thobei immortalised the boxing legend in their song King Kong Oshwile Ma. Unfortunately friends and family of the boxer interpreted the song as a mockery and subsequently both Thobei and Mafuya were badly beaten by his supporters one day at the Jeppe Railway Station — an assault severe enough to land Mafuya in Johannesburg General Hospital. (Molefe, Coplan) Before his suicide, Dlamini had been sentenced to prison for murdering his girlfriend and later became the subject of the famed musical King Kong in 1959.

|

| Thobei in 1993 by Mike Mzileni |

Azikhwelwa (We will not ride), a kwela tune by the Alexandra Casbahs, is attributed to Mafuya and Thobei and operates as a form of news item alerting people to the bus boycott of 1957 in Alexandra. Thobei opens the tune saying: “Yes, ladies and gentlemen, it was on Monday morning, the 7th of January, 1957 when everybody was shouting Azikhwelwa…” The bus boycott had been implemented by residents of Alexandra against the Public Utility Transport Corporation (more commonly known as PUTCO) over a rate hike of 4 to 5 pence. This spontaneous action lead to the formation of the Alexandra People’s Transport Action Committee (APTAC). Of course, during apartheid in South Africa, blacks were segregated into townships that were some distance from city centers and places of work and thus bus and train were, for many, primary modes of transport. Rate hikes would deeply affect every household’s bottom-line. With the boycott, residents chose other forms of transport to get to and from work, but most walked the 30km roundtrip journey. At its peak, 70,000 residents refused to ride the local buses and the action also spread to other townships including Newclaire and Mamelodi. The boycott lasted for at least three months and was only finally resolved on April 1st, 1957, when the 4 pence rate was restored. The protest drew the daily attention of the South African press and is generally recognized as one of the few successful political campaigns of the apartheid era. Read more about the campaign at Dan Mokoyane’s Blog here and more here.

|

| Sourced from SAHO (Drum Photographer, Bailey Archives) |

Likewise the track Asikhathali (We never get tired) by Ruth Molifi and the Starlight Singers opens with this annoucement: “This is the Troubadour Daily News! Many People are going to meetings everyday in Sophiatown and Alexandra. Some shout Azikhwelwa and some shout Ziyakhwelwa. It would be too cold to walk in winter. This is the song the people sing when they go to meetings… Asikhathali…” As Rob Allingham reveals, the tune features sisters Ruth and Doris Molifi, Mabel Mafuya and Mary Thobei on vocals with Cuthbert Matumba as ‘groaner.’ Thobei has an additional monologue where she states: “We don’t care if we are arrested. But we want our freedom. So pray people of Africa. We want our freedom.” Marks Mvimbe while coughing in the tune also moans “We are suffering going to meetings.” (Allingham)

Asikhathali is a classic of the struggle and this 1957 track probably marks the first time that it was recorded. Do a search for the term on YouTube and you will find many later renditions of the song, some professional, some really informal. Notable versions can be viewed here and here.

Other political classics by Mafuya include the tracks Cato Manor and Beer Halls, probably both recorded late in 1959 or very early in 1960. Cato Manor opens with a whistle that emulates the opening pitch of a radio broadcast and Mafuya announces “Zulu… Zulu… This is Durban Calling… This is Durban Calling…” (Similar to the opening broadcast of the day on radio.) “Women are fighting in Durban. They don’t want their men to drink in Beer Halls…” On the surface the song appears as a feminist critique, but rather it is a call to action against the government.

Cato Manor was the official name of an area that became home to a vibrant, informal settlement just outside Durban. To the local resident Cato Manor was known as Mkhumbane. Read more about the place and Todd Matshikiza’s 1960 musical of the same name here at Electric Jive.

The Durban City Council had long established a revenue system of selling alcohol to the black population exclusively through a series of beerhalls. The acquiring of alcohol from sources other than these official beerhalls was declared illegal for black South Africans and the residents of Cato Manor resented such control over what had been regarded as a tradition. Illegal brewing developed as a result, and in response the South African authorities regularly raided what were considered to be illicit businesses and made numerous arrests. Protests at such police action resulted and often led to violent clashes.

A nervous Durban City Council issued a proclamation in June 1958 to relocate inhabitants from Cato Manor to the more distant regions of Umlazi, Chatsworth and the newly developed township of Kwa Mashu. In 1959 the City Council declared Cato Manor a white zone under the Group Areas Act and in June began the process of forcibly moving residents.

At this time a response to the increased liquor raids in Cato Manor put into play a series of actions that soon spiraled into significant violence. It began on July 17, 1959 when a group of women gathered at the Cato Manor beerhall, threatening the men drinking there with sticks. This same group of women then proceeded to attack the central beerhall in Durban and a boycott of the beerhalls began. On July 18th, the following day, 3000 women gathered around the Cato Manor beerhall, and while clashing with police, set it on fire. It is significant to point out that these grievances were not over moral issues around the use of liquor, but rather the control of its production and sale. After more raids on January 23rd (some have it in early February) of 1960, an angry mob killed nine policemen at the Cato Manor Police Station.

In the song Beer Halls Mafuya announces in English: “They say do not buy potatoes! Do not eat fish and chips!” probably referring to the boycott of food items that were sold at beerhalls.

At Troubadour other political themes were tackled, most famously Dorothy Masuka’s song Dr. Malan with a line that translates as “Dr. Malan has difficult laws.” Allingham in the liner notes to the Masuka CD suggests that this marked the first occasion that an actual political leader was cited in a critical song. The disc sold well and was even played over the rediffusion service, but eventually the Special Branch came to the company requesting the master-tape and remaining copies. Fagan, the co-owner of the company had misleadingly claimed that he thought the song was a praise song for Malan. Records were confiscated but Fagan was able to hold on to the master recording. Ultimately Fagan and Katz did little with Police intimidation and remarkably continued to give Matumba significant latitude over content with Troubadour's ‘African’ catalogue.

Although Troubadour was bringing in significant sales, Allingham points out, that the technical quality of the actual product was quite poor when compared to the other major competitors. Still the studio was able to maintain an edge by using some unorthodox policies. For example it was well known that musicians under contract with rival companies were welcome to record, under-the-table, with pseudonyms if they needed cash. Many took advantage of this grey approach including Kippie Moeketsi, Ntemi Piliso and others. Sadly, none of the recording ledgers have survived and very few songs can be accurately dated with the full personal. (Allingham)

The company’s fall was as dramatic as its rise. After Matumba died in a car accident in May 1965, Troubadour began a rapid decline and by 1969 they were completely consumed by Gallo and ceased to exist.

Mafuya’s own singing career was severely affected after a botched thyroid operation in 1957. But still she was able to perform and towards the end of the decade formed a group with Thobei and Thandeka Mpambane known as the Chord Sisters. In 1958 the group was encouraged to join the King Kong crew and Mafuya played a small acting role in the classic 1959 play. After that success she was invited to travel with the cast to London and stayed there for a year. Mafuya eventually returned to South Africa and continued with her acting career. She would later perform in the hit TV sitcom Velaphi.

While her singing career turned out to be quite short, Mafuya was nevertheless prolific and the tracks featured below reveal just a small part of her excellent output during a turbulent but also dynamic time. For a provisional discography of Mafuya visit flatint.

Postscript: Mafuya in her 1993 interview with Molefe, laments over the fragmentation of the music tradition in South Africa: “The young sisters nowadays seem to have no idea of where they come from. They don’t know us. But who can blame them. Nobody told them about us.” (Molefe)

MABEL MAFUYA ON 78 RPM

(1956 - 1960)

(Flatinternational / Electric Jive, FXEJ 9)

01) MABEL MAFUYA AND HER GIRLFRIENDS

Regina - 1956 (Matumba, Troubadour, AFC 364, RSA)

02) MABEL MAFUYA AND HER GIRLFRIENDS

Baba - 1956 (Matumba, Troubadour, AFC 364, RSA)

03) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE SATCHMO SERENADERS

Tsili - 1956 (Monamoeli, arr. Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 387, RSA)

04) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE SATCHMO SERENADERS

Satchmo Special - 1956 (Monamoeli, arr. Mafuya, Troub., AFC 387)

05) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE SATCHMO SERENADERS

Khumbula - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 416, RSA)

06) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE SATCHMO SERENADERS

Woza Skanda Mayeza - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 416, RSA)

07) MABEL MAFUYA

Bumba Lo Ntsimbi - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 417, RSA)

08) MABEL MAFUYA

Ungibalele - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 417, RSA)

09) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE STARLIGHT BOOGIES

Heyta! - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 427, RSA)

10) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE STARLIGHT BOOGIES

Kehlela - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 427, RSA)

11) ALEXANDRA CASBAHS

Azikhwelwa - 1957 (Mafuya, Thobei, Troubadour, AFC 429, RSA)

12) ALEXANDRA CASBAHS

Alexandra Special - 1957 (Mafuya, Thobei, Troub., AFC 429)

13) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE STARLIGHT SERENADERS

Charlie - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 434, RSA)

14) MABEL MAFUYA AND THE STARLIGHT SERENADERS

Chomie - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 434, RSA)

15) RUTH MOLIFI AND THE STARLIGHT SINGERS

Asikhathali - 1957 (Molifi, Troubadour, AFC 440, RSA)

16) RUTH MOLIFI AND THE STARLIGHT SINGERS

Mfana - 1957 (Mafuya, Troubadour, AFC 440, RSA)

17) MABEL MAFUYA

Silindele Christmas - 1959 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 534, RSA)

18) MABEL MAFUYA

Sisaphila - 1959 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 534, RSA)

19) MABEL MAFUYA

Cato Manor - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 567, RSA)

20) MABEL MAFUYA

Beer Halls - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 567, RSA)

21) MABEL MAFUYA

Sibarie - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 579, RSA)

22) MABEL MAFUYA

Umtata - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 579, RSA)

23) MABEL MAFUYA

Happy Xmas - Happy New Year - 1960 (Ngubane, Troub., AFC 584)

24) MABEL MAFUYA

Jabulani Xmas - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 584, RSA)

25) MABEL MAFUYA

Ngi Yeka - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 608, RSA)

26) MABEL MAFUYA

Itlalo Ya Lizwe - 1960 (Ngubane, Troubadour, AFC 608, RSA)